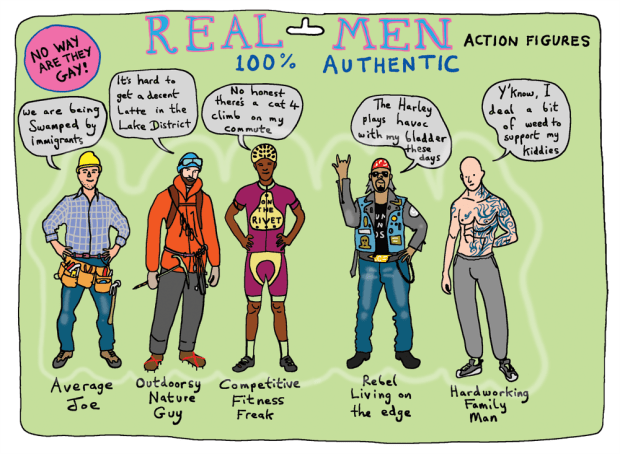

We all know one, many of us identify as one, most of us have loved one, some have hated one: Men. But what makes a man? How does masculinity operate? And could it be in need of an urgent upgrade? These are questions Grayson Perry discusses in his book ‘The Descent of Man’. Perry is an English contemporary artist, broadcaster and writer. He is well known for his ceramic art and for cross-dressing as Claire. The Descent of Man is a small book with beautiful illustrations. Although small, the book’s message is ambitious: there is something seriously wrong with the way we perceive masculinity and we better fix it, quick. Perry defines masculinity as a set of habits, traditions and beliefs historically associated with being a man; something deeply interwoven in men’s (and women’s I would add) psyche.

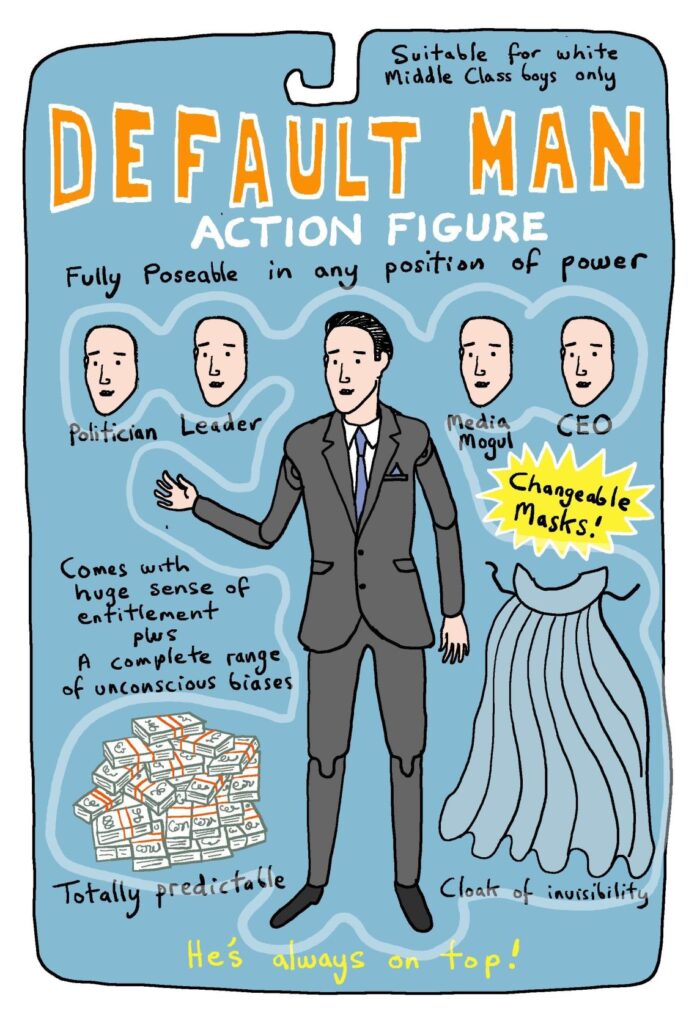

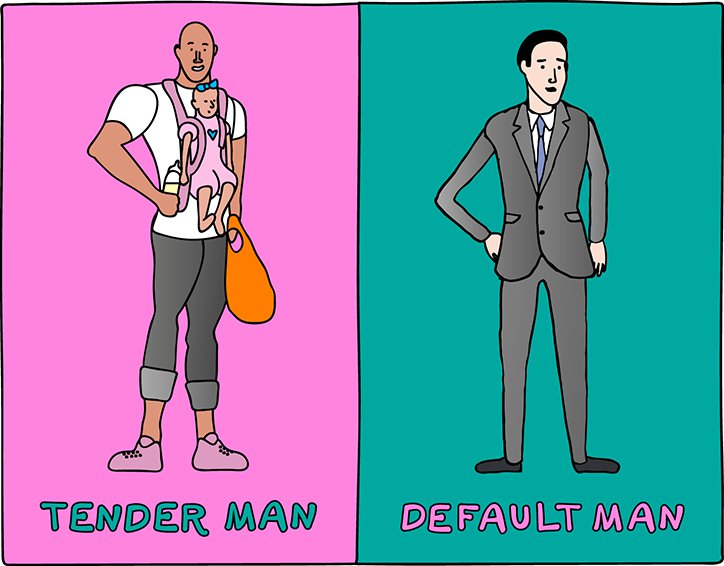

In the book he is not afraid of categorizing men, one of which being The Default Man. Perry describes Default Men as a tribe. It’s a tribe that everybody knows, but nobody really bothers to investigate. In the UK, the Default Man’s tribe makes up around 10 per cent of the population, globally around 1 per cent. And yet, this tribe rules the world. They are the majority in governments, in boardrooms and in media. Obviously here Perry is talking about white, middle-class, often middle-aged, heterosexual men. “If you are a Default Man, you look like power.” “The very aesthetic of seriousness has been monopolized by Default Man,” he writes. “In people’s minds, what do professors look like? What do judges look like? What do leaders look like? It is going to be a while before the cartoon cliché of a judge is Sonia Sotomayor or that of a leader is Angela Merkel.” But most Default Men will not feel, or admit, of belonging to this specific tribe. Mainly because they see themselves as individuals: a result of the capitalist ideology many believe in. Here being an individual means that what one has achieved, has been accomplished due to personal efforts and not because of belonging to a certain group.

The Default Man is the embodiment of neutrality: he is rarely under existential threat and therefore his identity is fairly unexamined (and thus very interesting for anthropologists). “If Default Men approve of something it must be good, and if they disapprove it must be bad, so people end up hating themselves for being female, gay, black, silly or wild.”

Perry has called the book The Descent of Man because he suggests that as women rise to their just levels of power, some men shall fall. More and more women are getting the positions they deserve. But it’s still happening way too slow. If we keep this pace, it will still take a hundred years before the UK parliament is 50 per cent female. Perry would like to see that happen at least within his lifetime. One of the frequently offered solutions is so-called ‘positive discrimination’. But such ideas are also met with a lot of critique. According to Perry such critique is: “the wail of someone who is having his privilege taken away”

This statement about privilege I found interesting, as it is what I frequently hear when talking to others about for example gender quotas. Personally I would not use the concept of positive discrimination, because there is simply no such thing as positive discrimination: discrimination is inherently negative. An often used counter argument to gender quotas is: “everybody should be treated the same, quotas are then privileging women.” Here privilege seems to be a word that is both frightening, and misunderstood. We tend to think that privilege means that we did not deserve what we have. That we did not work hard enough. That we did not encounter challenges in life. But as Emmanuel Acho explains it: privilege simply means that your skin color, or gender in this case, never hindered you in achieving what you wanted. And acknowledging this privilege does not make you a worse, or less hard working, human being. What kind of human beings we are is shaped by how we use these privileges. Like trying to create privileges for others too, through gender quotas for example.

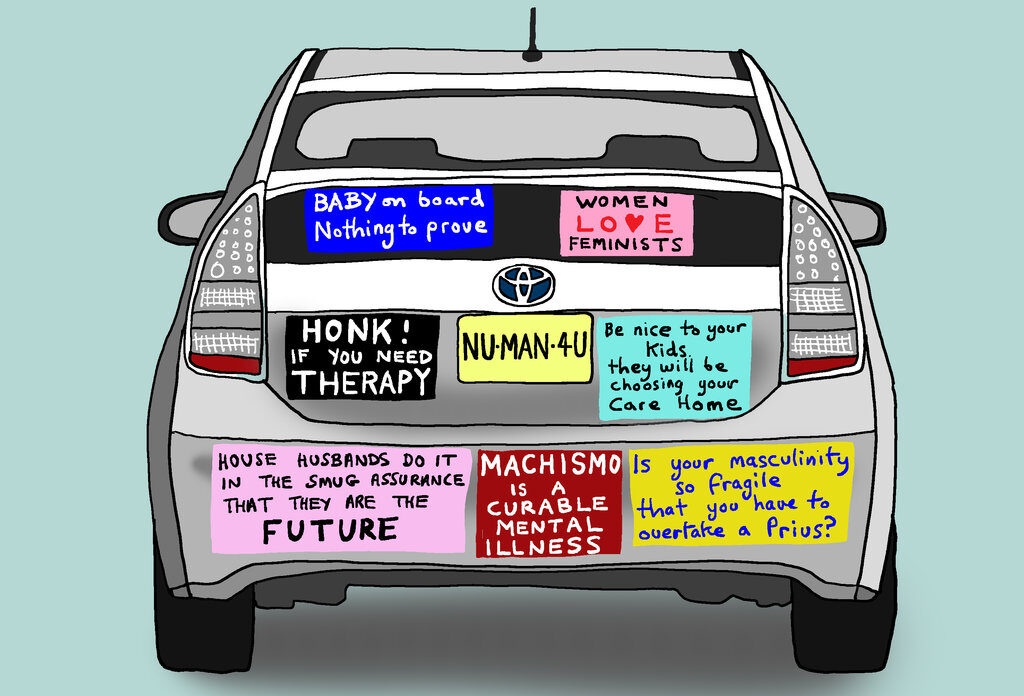

As masculinity is a set of behaviors and conditioned feelings, its characteristics and boundaries are also constantly changing, Perry writes. Today, millennials or ‘digital natives’ seem to be more at ease with gender fluidity. In the last years in we have witnessed a high-profile move towards trans awareness and acceptance. Particularly well-educated, young, metropolitan men seem less afraid of appearing gay. However, according to Raewyn Connell, writer of ‘Masculinities’ (1993) the idea that we live at a moment where a traditional male sex role is softening is as drastically inadequate as the idea that a ‘natural’ masculinity is being recovered.

Grayson Perry would like to see a vision of masculinity that is not just thrilling and sexy, but one that celebrates true everyday happiness that comes from stable intimate relationships and a meaningful role in the world. What most urgently needs to change is the downplaying of men’s emotional complexity – the idea that men are just not that that ‘complicated’.

To get there he states, men should critically rethink their relationship with power, performance and violence. Because “most violent people, rapists, criminals, killers, tax avoiders, corrupt politicians, planet despoilers, sex abusers and dinner-party bores, do tend to be, well… men”. Unfortunately men are not only more often the perpetrators, but also the victims, as they are up to three times more likely to commit suicide. Such numbers are according to Perry only the tip of the iceberg of lonely, depressed men unable to reach out for meaningful human intimacy. Because the problem is not, and has never been about ‘being a man’. It is the role society assigns to it.

The book is such an easy and pleasant read. It is a good mix of academic feminist thinking and Perry’s lived experiences. While he strongly critiques some aspects of masculinity, he certainly does not critique men. Although he often mentions the UK, an introduction to where his viewpoints come from would have improved the book. It is written from a completely Western perspective which at times makes his arguments seem generalizing. And then I would suggest that there is no such thing as plural masculinity: there are just as many masculinities as there are men. What there is, is Western hegemonic masculinity. In my opinion a brief explanation of the backdrop of his views and arguments would have strengthened the message of his book.

Maybe that is also how the end of the book could have become stronger: what kind of society do we want to create by reviewing our ideas of masculinity? What are ‘successful’ examples? Perry mentions Barrack Obama as exemplary for being in touch with his masculinity and emotions, but what makes Obama’s view of masculinity so unique? Or is it mainly unique due of his position? And what kind of role should women have in this shift? Aren’t we contributing just as much to ‘toxic’ masculinity? As an anthropologist such calls for change always leave me with a lot of questions. Luckily enough in this case that is a good thing, as during the next years this is what I will be researching.

The Descent of Man is a small, smart book that I can recommend to anyone interested in what it means, or what it can mean, to be a man in Western society. It is a particularly interesting book for starting discussions that might lead us towards shifting perspectives of masculinities. Or as Perry says it: “We should shout from rooftops that masculinity can be anything you want it to be.”